Scientists have discovered a new creature off the coasts of Sydney that could be a “secret weapon” in the fight against climate change.

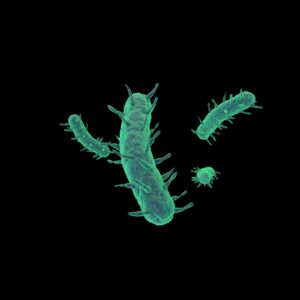

According to researchers at the University of Technology Sydney, the single-celled microbe has a taste for carbon and could be used to help balance emissions in our atmosphere.

The tiny predator uses photosynthesis, just like plants, to take energy from the sun, a process that also absorbs carbon.

What makes this miniature microbe so incredible, though, is it then secretes a thick, carbon-rich mucus that attracts and traps other microbes. Then, it eats them for energy, too, before letting the heavy liquid sink to the bottom of the ocean.

At the bottom of the ocean is where the real magic happens, as the mucus then stays there, allowing the ocean to absorb more carbon from the atmosphere than it usually would.

According to marine biologist Dr Michaela Larsson, who led the research published in the journal Nature Communications, this type of behaviour has never been seen before.

“Most terrestrial plants use nutrients from the soil to grow, but some, like the Venus flytrap, gain additional nutrients by catching and consuming insects,” said Dr Larsson.

“Similarly, marine microbes that photosynthesise, known as phytoplankton, use nutrients dissolved in the surrounding seawater to grow.”

“However,” she added, “our study organism, Prorocentrum cf. balticum, is a mixotroph, so is also able to eat other microbes for a concentrated hit of nutrients, like taking a multivitamin.

“Having the capacity to acquire nutrients in different ways means this microbe can occupy parts of the ocean devoid of dissolved nutrients and therefore unsuitable for most phytoplankton.”

The species is estimated to be capable of sinking up to 150 million tonnes of carbon every year.

For context, previous research has suggested that around 10 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide will need to be removed from the atmosphere every year until 2050 if we want to meet our climate goals.

Professor Doblin noted, “This could be a game-changer in the way we think about carbon and the way it moves in the marine environment.”