After two weeks at COP26, followed by several hours of arduous negotiations, the world has come together to produce the Glasgow Climate Pact.

The document doesn’t seek to replace the Paris Agreement but instead bolster it, aiming to keep global warming to 1.5C compared to the pre-industrial era.

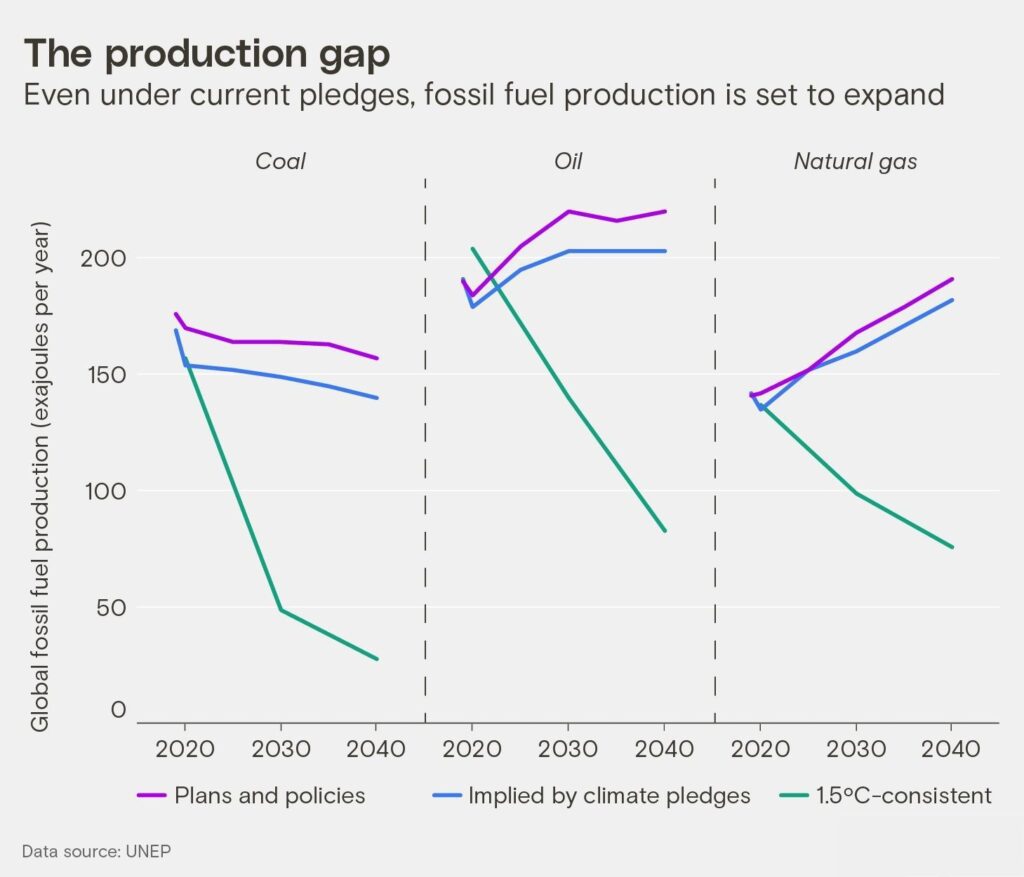

For the first time ever, the final COP text references “coal” and “fossil fuels”. Despite being the leading causes of climate change, they have been relatively taboo before on the international stage.

Another major first is that nature is finally being recognised as both a problem we need to solve and a potential solution.

This was done through $20bn in commitments of both public and private money for forest protection, and a pledge from more than 100 countries to reverse deforestation by 2030 at the latest.

The decision text emphasises the importance of this, noting that we need to protect, conserve, and restore our natural environment if we are to achieve our climate goals.

Whether we can label this COP as ‘successful’, however, is a rather difficult question.

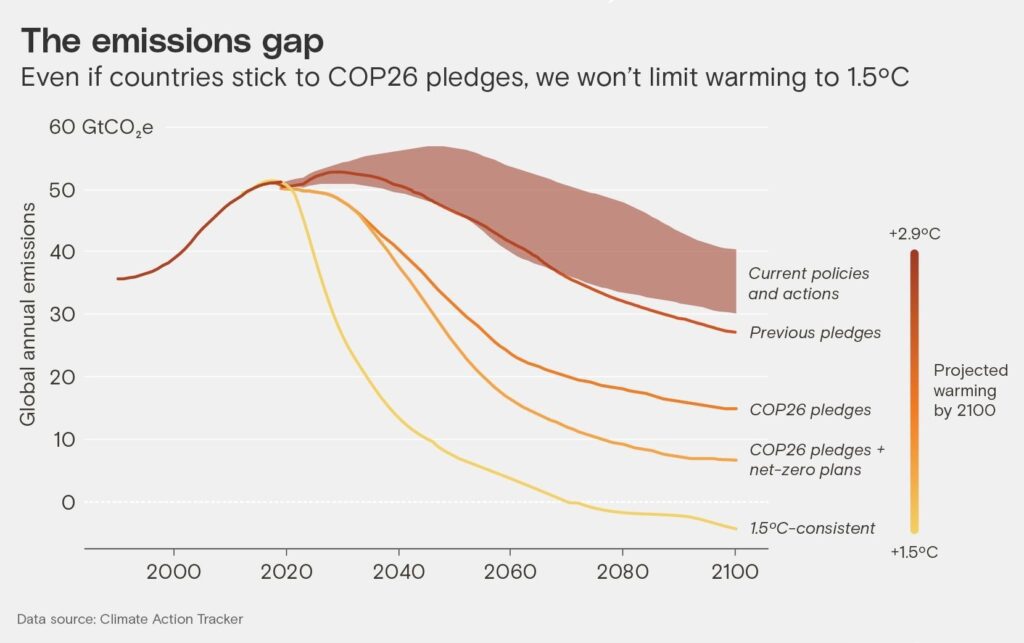

The Paris Agreement in 2015 changed our forecasted trajectory of a 6C rise by the end of the century down to 3.7C, an outcome that would still be catastrophic for humanity. COP26 was needed to change this.

Climate Action Tracker, a climate analysis firm, has helpfully analysed all of the official plans countries have submitted to the U.N. up to and during the past two weeks.

They found that if all the targets for 2030 were achieved, the world would still heat up by around 2.4C.

Given that Prime Minister of Barbados Mia Amor Mottley said a rise of 2C would be a “death sentence” for her country on the very first day of the summit, it’s definitely clear that the plans don’t go far enough.

Even the “optimistic scenario”, which takes into account the less-official statements of countries on achieving net-zero by 2050, still puts warming at 1.8C and above the Paris target.

Beyond warming, other areas of the report have been lacklustre or, in some cases, entirely missing.

For example, a draft text earlier last week included the lines “Calls on parties to accelerate the phasing-out of coal and subsidies for fossil fuels.”

In the final Pact, however, the language was change to “the phase-down of unabated coal”, allowing for coal plants with carbon capture systems.

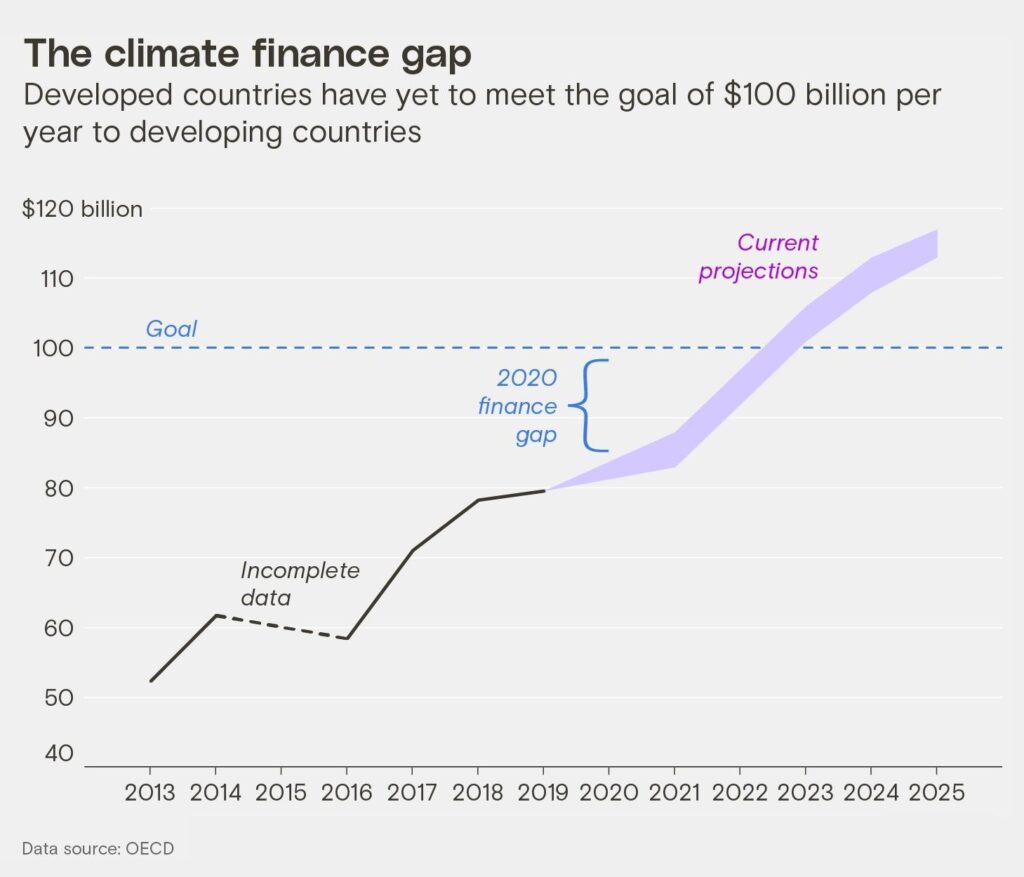

Financing was a particularly challenging point in negotiations with few results.

In Glasgow, countries were expected to chart a faster path to the $100bn goal that has already passed its deadline. Plans were also expected on how much finance should be allocated after 2025.

There were some pledges, such as Japan promising an extra $10bn and Scotland providing the first-ever contribution to a fund to compensate countries who have suffered from climate disasters.

In the final agreement, however, it only “notes with deep regret” that the $100bn target hasn’t been met and “urges” developed nations to follow through on the promise as quickly as possible.

Even if it were to be met, negotiators for developing countries have repeatedly stated that this is not enough.

In a speech, Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India said that rich nations should be supplying $1 trillion in finance by 2030, and a group of African nations pushed for at least $1.3 trillion every year after 2025.

Developing countries have also stated their desire for funds to be split more evenly between adaptation (helping them deal with sea-level rise and extreme weather events) and mitigations (switching to clean energy and cutting emissions).

While the conference did see a record $365m in contributions to a U.N. fund focused on adaptation, the amount pales in comparison to what is needed.

The cover decision does call upon developed nations to “at least double” their contributions to adaptation, but this is reliant upon each country deciding to follow through.

It’s clear from the end of negotiations that much more work still needs to be done.

There is hope, however, as thanks to a strong push by some of the most vulnerable countries, new agreements and pledges will be made every year rather than every five.

This is a much-needed tightening of the system and will hopefully mean that even more change can be expected when the nations reconvene in Egypt next year.

Whether this COP can be labelled as a success, however, mostly depends on your point of view.

Many environmentalists and green groups are angry with the outcome, stating that these efforts are not even remotely close to what we could and should be doing.

Yet, stopping climate change is not an easy feat. It requires the whole system to change, even in countries that depend upon fossil fuels, or in sectors where we don’t have the technology available to make them green.

On top of that, the window of time where success is even possible is constantly shrinking.

The final deal is, as it was always going to be, a compromise. These steps are a step in the right direction, and definitely better than doing nothing.

The true success of COP26, however, will not be known for years, and will require each and every one of us to do our part and hold our countries accountable.